CFEngine tutorial

Overview

CFEngine is a configuration management tool that allows a system administrator to configure multiple hosts continuously. CFEngine runs as a client/server application. The server provides new configurations, or policy, while the client works to ensure that a client host conforms to them.

The policy is written the descriptive language of CFEngine. This language describes what the running state of a host or hosts should be. The agent, over one or more iterations, makes the client conform to this policy in a convergent manner.

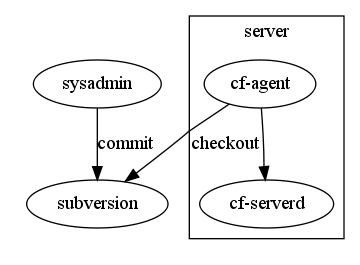

Figure: CFEngine cycle

As seen in the figure CFEngine agents (cf-agent) contact the policy server (cf-serverd) for new or changed policies or files. This is a “pull” method in which the client contacts the server instead of a “push” method where the server contacts the client. Using the “pull” method allows the client to operate autonomously in the absence of the server. This allows for greater reliability.

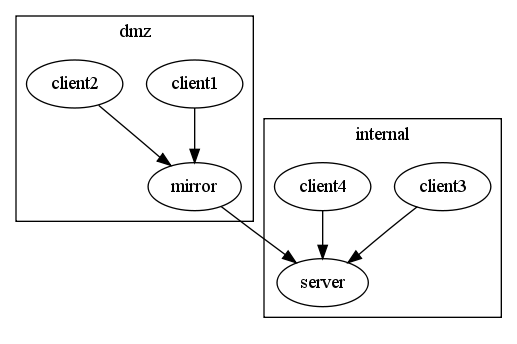

The security implications often associated with pull clients can if desired by alleviated by the use of policy mirrors (see figure).

Figure: CFEngine Mirror

CFEngine 3 consists of a number of components. As this is an introductory tutorial some components will not be covered here.

- cf-agent Active agent

- cf-execd Scheduler

- cf-graph Graph data extractor

- cf-know Knowledge modelling agent

- cf-monitord Passive monitoring agent

- cf-promises Promise validator

- cf-runagent Remote run agent

- cf-serverd Server that acts mostly like a file server for cf-agent.

- cf-report Self-knowledge extractor

The daemon formally called cfenvd in previous versions of CFEngine is now called cf-monitord.

CFEngine files are normally located in /var/cfengine. CFEngine will create some directories automatically in this location. The two important ones that must be created by hand are /var/cfengine/bin and /var/cfengine/inputs. The bin directory contains the binary components listed earlier. This location allows for CFEngine to be more self contained and fault tolerant. For example, the traditional location of /usr/local/bin is not always a local file systems and therefore less reliable.

The inputs directory contains all of the configuration files that CFEngine will use to maintain itself and the client hosts. The majority of work with CFEngine will involve files located here. The mandatory files are failsafe.cf, update.cf and promises.cf. Other files are user defined and will be discussed later.

Basic example

Here I’ll present a basic example of CFEngine. Functionally it will do little more than ensuring that CFEngine is running. What is learned from this example will be applicable to more practical uses.

CFEngine can run on virtually any UNIX host. It can also run on Windows with the help of the Cygwin environment. One can either choose to install CFEngine from a distributions application repository (e.g. Debian or Freshports) or download the source from CFEngine.org and compile it. The source code contains all of the necessary instructions to compile and install CFEngine. Note that there are some dependencies that must be met before CFEngine can be built. The source code contains information on these also. An automated distribution install will take care of these automatically.

Directories and files

- /var/cfengine/bin CFEngine binaries.

- /var/cfengine/inputs Main configuration files.

- /var/cfengine/ppkeys Storage for authentication keys.

- /var/cf-masterfiles The master files, on the server, that agents will request from the server.

/var/cf-failsafe A backup of important CFEngine files to allow for automatic recovery.

promises.cf This is the main configuration file. The agent will automatically start with this file.

- update.cf This is a simplified file whose purpose is to ensure the agent is configured properly so that it can do its job.

- failsafe.cf This file is run by the agent if other files are missing or contain errors. This gives the agent the ability to recover itself from failure.

- cf-server.cf This file configures the CFEngine server. It can be named anything but choosing this name is logical.

- cf-execd.cf This file will configure the CFEngine executor. Like cfserver.cf this file could be named something else.

- cfbackup.cf This makes a local backup of CFEngine to ensure the agent can recover from serious data loss.

- crontabs.cf This manages host crontables.

- library.cf This contains a collection of reusable code similar to a subroutine library.

Key authentication

CFEngine agents authenticate with a server via key exchange. The cf-key binary will create a public and private key pair. This is done for every server and client. For two hosts to authenticate each must have a copy of the other’s public key file. This exchange is normally done manually but CFEngine may be configured to do this one time only. Please refer to the reference manual for more information.

The syntax of CFEngine files is relatively simple and somewhat Perl like. However, CFEngine tends to be more sensitive to white space.

- Sections are contained withing brackets.

- Commas separate parts of the same action.

- Actions are ended with a semicolon.

- Body part lines end with semicolons.

- Variables are identified by $ and usually contained in brackets to separate them from surrounding text.

- Most user defined information is contained within double quotations.

- Comments begin with # or can be included in the promise so that CFEngine will print them during a run (comment => "My comment").

If you follow the examples contained in this paper you’ll not have to worry much about syntax.

There are three CFEngine commands you'll need to use for these examples. The server is started by cf-serverd. After starting it will fork to the background. The command cf-promises will validate a CFEngine policy. It is a good way to check for syntax errors. Finally cf-agent is the agent that will do the work. Using the -v and -n options will allow you to test and debug your policy.

The promises.cf file is the first file that CFEngine reads.

1 #######################

2 # promises.cf

3 #######################

4

5 body common control {

6 bundlesequence => {

7 "update",

8 "executor",

9 "server",

10 "crontabs",

11 "cfbackup" # should be last

12 };

13

14 inputs => {

15 "update.cf",

16 "library.cf",

17 "cf-serverd.cf",

18 "cf-execd.cf",

19 "crontabs.cf",

20 "cfbackup.cf"

21 };

22 }

23

24 bundle common g{

25 vars:

26 "masterfiles" string => "/var/cf-masterfiles";

27 "inputs" string => "${masterfiles}/config/branches/cf3/inputs";

28 "workdir" string => "/var/cfengine";

29 # for HA add more policy hosts

30 "phost" string => "192.168.0.1";

31 }

32

33 body agent control {

34 # Do not rely on DNS

35 skipidentify => "true";

36 }

Lines 5-12 define the bundlesequence. Previously CFEngine determined actions via the actionsequence. In CFEngine 3 the sequence of actions is defined by CFEngine and is based on the previous experience of developers and users. CFEngine 3 now offers something called a bundle. A bundle is a list of actions (e.g. files, shell commands, processes) grouped for a single purpose. These bundles will be executed in the order defined by the bundle sequence.

- update Update inputs if the policy server has changes to distribute.

- executor: Configure cf-execd.

- server: Configure cf-serverd.

- crontabes: Configure a client host’s crontables.

- cfbackup: Backup CFEngine’s configuration files for automated recovery.

Lines 14-21 import other configuration files. A CFEngine policy can become very large. Separating the policy into distinct files makes management easier. In this case we separate mostly into bundles with the exception of library.cf which hosts reusable code.

Lines 24-31 define some global variables. We will be able to refer to these variable throughout our policy (e.g. ${g.masterfiles}).

Lines 33-35 instruct CFEngine to not use DNS to attempt to authenticate clients and servers. This is entirely optional and depends on how reliable and trustworthy your DNS service is.

The sole purpose of update.cf is to ensure that CFEngine has the latest policy files. Once you have this file working do not change it unless absolutely necessary.

1 #######################

2 # update.cf

3 #######################

4

5 bundle agent update {

6

7 vars:

8

9 "masterfiles" string => "/var/cf-masterfiles";

10 "inputs" string => "${masterfiles}/config/branches/cf3/inputs";

11 # for HA add more policy hosts

12 "phost" string => "192.168.0.1";

13

14 files:

15

16 # Fix directories

17 "/var/cfengine/."

18 create => "true",

19 perms => usystem("0700");

20

21 "/var/cfengine/bin/."

22 create => "true",

23 perms => usystem("0700");

24

25 "/var/cfengine/ppkeys/."

26 perms => usystem("0700");

27

28 # Copy inputs

29 "/var/cfengine/inputs"

30 perms => usystem("0600"),

31 copy_from => umycopy("${inputs}"),

32 depth_search => urecurse("inf");

33

34 # Copy binaries

35 "/var/cfengine/bin/cf-failsafe.sh"

36 perms => usystem("0700"),

37 copy_from =>

38 umycopy("$(masterfiles)/config/branches/cf3/bin/cf-failsafe.sh");

39

40 debian_5.64_bit::

41 "/var/cfengine/bin"

42 perms => usystem("0700"),

43 copy_from =>

44 umycopy("$(masterfiles)/config/branches/cf3/bin/debian-5-64"),

45 depth_search => urecurse("1");

46 }

47

48 body depth_search urecurse(d) {

49 depth => "${d}";

50 exclude_dirs => { "\.svn" };

51 }

52

53 body perms usystem(p) {

54 mode => "${p}";

55 owners => { "root" };

56 groups => { "root" };

57 }

58

59 body copy_from umycopy(from) {

60 source => "${from}";

61 servers => { "${phost}" };

62 compare => "digest";

63 verify => "true";

64 # purge => "true";

65 }

The following will jump around a little in an attempt to give the reader the entire picture.

Line 5 begins the bundle, for the agent, called “update”.

Lines 7-12 define some local variables. Recall that we define similar variables globally in promises.cf. The purpose of update.cf is to keep the configuration functional and up to date even if other files are missing or damaged. Thus this file is designed to be self contained. It is also run first in the bundle sequence so that policies can be updated or repaired before they are in turn run.

Line 14 begins the files action. Files actions can involve creation, setting permissions, copying, deleting or even editing.

Lines 17-19 ensure that the permissions of /var/cfengine are set to mode 0700. Line 18 will actually create the directory if it is missing. Line 19 calls a “body part”. Body parts a somewhat like functions or subroutines. In this instance the string 0700 it past to the part usystem which is defined on lines 54 to 58.

Line 53 identifies the body part as being used for permissions (perms), names it (usystem) and defines what variable will receive the passed data (p).

Line 54 sets the mode using the variable “p” which was passed from above.

Lines 55-56 set the user and group ownerships.

Line 57 ends the body part.

Lines 21-26 define the directories /var/cfengine/bin and /var/cfengine/ppkeys in the same way as /var/cfengine was defined.

Lines 29-32 define the contents of /var/cfengine/inputs.

Line 30 sets the permissions using the “usystem” body part. Note that CFEngine will automatically add the executable bit to directories.

Line 31 sets the copy source and calls the body part “umycopy” and passes the variable “inputs” to it. The variable inputs was defined on line 10. It tells CFEngine the location of the source files that are to be copied to /var/cfengine inputs.

Lines 59-65 define the copy_from body part named “umycopy”.

Line 59 identifies the body part, its type (copy_from), its name (umycopy) and what variable to store its passed data in (from).

Line 60 defines the copy source with the contents of the “from” variable.

Line 61 defines the source server from the “phost” variable.

Line 62 instructs CFEngine determine if a file needs updating from the source by comparing the MD5 hash of each.

Line 63 instructs CFEngine to verify the copied file with the source before committing the copy.

Line 64 instructs the agent to delete any files at the destination that are not at the source. In effect this removes old files.

Line 32 sets the depth of the recursive copy and calls the body part “urecurse” and passes the string “inf” to it.

Lines 48-51 define the “urecurse” body part.

Line 48 identifies the body part, its type (depth_search), its name (urecurse) and the variable that will take the data passed to it (d).

Line 49 define the depth of the directories to compare. From line 32 this is set to infinite. It could be set to something else which allows for control similar to the UNIX “find” command.

Line 50 instructs the search to exclude any paths containing the string “.svn”. That string is a regular expression so the period must be escaped for it to be taken literally. This line is used because our master files, the source of this copy, are found in a Subversion working copy. The .svn directories found in Subversion working copies do not need to be copied.

Line 51 ends the “urecurse” body part.

Line 35 defines another copy but this time only a single file: cf-failsafe.sh.

Line 40 defines a class of host. Until now we have not defined any classes. Thus any agent would run the actions defined. In this case we define a class of “debian_5.64_bit” to instruct the agent to run the following actions only on Debian 5 hosts that are 64 bit. When the agent runs it will determine many hard classes including the UNIX distribution automatically.

Line 45 defines the depth of the search body part as 1 in this case because we only wish to copy that single file.

CFEngine defaults to failsafe.cf if other regular files such as promises.cf have errors. There are many ways that one might be creative with this file.

1 #######################

2 # failsafe.cf

3 #######################

4

5 body common control {

6 bundlesequence => { "update" };

7 inputs => { "update.cf" };

8 }

This file simple tells CFEngine to run the update.cf file.

When we discussed update.cf we showed several body parts that acted similarly to fuctions or subroutines. Since update.cf is meant to be self contained specialized body parts were included in that file. Normally it is efficient to reuse the same body parts as much as possible throughout the the CFEngine policy. This library.cf file contains a collection of resuable parts. The makers of CFEngine now offer a large library of body parts ready for use. This is called the Community Open Promise Body Library. It can be a realy time saver.

1 # Library of commond code

2

3 body depth_search recurse(d) {

4 depth => "${d}";

5 # exclude .svn revision control files

6 exclude_dirs => { "\.svn" };

7 }

8

9 body perms system(p,u,g) {

10 mode => "${p}";

11 owners => { "${u}" };

12 groups => { "${g}" };

13 }

14

15 body copy_from mycopy(from,server) {

16 source => "${from}";

17 servers => { "${server}" };

18 compare => "digest";

19 }

Lines 3-7 define the recursive search body part. It is defined similarly to the part in update.cf. Only the name is different. Note the comment in line 5.

Lines 9-13 define the body part that sets file permissions. Unlike the part in update.cf this part takes three arguments: the mode, owner and group.

Lines 15-19 define the part that sources where files are copied from. Here we pass the source path and the server. Note that on line 17 the server is defined more like an array. This allows for the use of redundant servers. Line 18 defines that copies are compared using MD5 hashes.

The file cf-serverd configures the cf-serverd process.

1 body server control {

2 # Do not use DNS

3 skipverify => { "192.168.0.*" };

4 allowconnects => { "192.168.0.0/24" };

5 allowallconnects => { "192.168.0.0/24" };

6 maxconnections => "5";

7 logallconnections => "true";

8 trustkeysfrom => { "192.168.0.1" };

9 bindtointerface => "192.168.0.1";

10

11 cfruncommand =>

12 "${g.workdir}/bin/cf-agent";

13 allowusers => { "root" };

14

15 }

16

17 # ensure server is running.

18 bundle agent server {

19 processes:

20

21 "cf-serverd"

22 restart_class => "start_cfserverd";

23

24 commands:

25

26 start_cfserverd::

27 "${g.workdir}/bin/cf-serverd";

28 }

29

30

31 bundle server access_rules {

32 access:

33 "${g.masterfiles}"

34 admit => { "192\.168\.0\..*" };

35

36 # All policy hosts to 'push'.

37 "${g.workdir}/bin/cf-agent"

38 admit => { "${g.phost}" };

39 }

40

41 body runagent control {

42 hosts => {

43 "192.168.0.1"

44 };

45 }

Line 1 begins the control body for the server. Control is for defining required settings.

Line 3 instructs the server to not attempt to verify the given IP range via DNS lookups. If you have a very good DNS service you may not want to define this.

Line 4 defines a network from which the server will answer connections.

Line 5 defines the maximum connections the server will allow at one time.

Line 6 defines the maximum number of connections allowed from each node.

Line 7 tells the server to log all connections. This is very useful for auditing and troubleshooting.

Line 8 tells the server to trust the key given to it from the stated IP address. I only include this as it was needed for my lab setup. In production it may be better to not state this and exchange all keys by hand.

Line 9 binds the server to a particular network interface. Unless your host has multiple IP addresses you’ll not need this.

Lines 11-12 define the command that will be run when the run agent (cf-runagent) contacts the server. The run agent allow push like actions. When run on the policy host the run agent will contact the server process on each client and instruct it to run the agent now to pull updates from the policy server.

Line 13 allows the root user to be able to use the run agent.

Line 18 begins a bundle meant for the cf-agent.

Line 19 begins a processes action.

Line 21 tells the agent to search the processes table (e.g. ps -aux) for the string “cf-serverd”.

Line 22 states that if the string from line 21 is not found then define the class “start_cfserverd”.

Line 24 begins a commands action.

Line 26 calls the class “start_cfserverd” meaning that only agents with that class may issue the next command.

Line 27 defines the command to be run should the agent belong to the class in line 20.

Lines 19-27 simply stated, tell the agent to start the cf-serverd process if it is not already running.

Line 31 begins a server bundle called access_rules. This allows for a more fine grained control of what the agent may ask for from the server.

Line 31 begins an access action.

Line 33 lists a path on the server that the agent may access.

Line 34 defines the IP address, in a regular expression, that the agent must have in order to access the path defined in line 27.

Line 37 lists a path to the agent binary.

Line 38 allows the policy host(s) to access this binary. This allows the run agent on the policy server to invoke the agent on the clients for the pseudo push. cf-execd.cf

Recall that the executor, cf-execd, is a process that sits in the back ground and starts cf-agent at defined intervals.

1 #######################

2 # cf-execd.cf

3 #######################

4

5 body executor control {

6 splaytime => "1";

7 mailto => "root@example.com";

8 smtpserver => "192.168.0.1";

9 mailmaxlines => "100";

10 schedule => { "Min15_20", "Min45_50" };

11 executorfacility => "LOG_DAEMON";

12 }

13

14 bundle agent executor {

15

16 processes:

17

18 "cf-execd"

19 restart_class => "start_cfexecd";

20

21 commands:

22

23 start_cfexecd::

24 "${g.workdir}/bin/cf-execd";

25

26 }

27

28 # cf-execd is also added to the root

29 # cron table in the cron inputs section.

Line 5 begins the control body for the executor.

Line 6 defines a random wait time (about 1 minute) that each executor will wait when it”s schedule time is before it starts cf-agent. This it to prevent all agents from connecting to the server at exactly the same time. If you have a deployment of 1000 hosts this is a good thing.

Line 7 defines the address that any reports should be mailed to.

Line 8 defines the SMTP server that the mail from line 7 should be sent to.

Line 9 defines the maximum size of the email. DDOSing a mail server is never a good thing.

Line 10 defines when the executor should start cf-agent. In this case twice per hour during the alloted window. Note that exact timing is not a goal of CFEngine. It is meant to work gradually.

Line 11 defines the syslog facility for the executor.

Line 14 begins a bundle that cf-agent will use to ensure that executor is working properly. This is similar to the agent server bundle in cf-serverd.cf.

Lines 16-19 tell the agent to look for the process “cf-execd” and define a restart class if it fails.

Lines 21-24 tell the agent to start the executor, cf-execd, if lines 16-19 did not find an already running process. crontabs.cf

This file configures cron tables for hosts.

1 #######################

2 # crontabs.cf

3 #######################

4 # IMPORTANT

5 # Please test crontabs before deploying them.

6

7 bundle agent crontabs {

8 vars:

9 "crontabs" string => "/var/spool/cron/crontabs";

10

11 files:

12 "${crontabs}/root"

13 perms => system("0600","root","root"),

14 copy_from =>

15 mycopy("${g.masterfiles}/config/branches/cf3/crontabs/ettin/root","${g.phost}");

16 }

Line 7 begins an agent bundle called crontabs.

Lines 8-9 define the variable “crontabs”.

Line 11 begins a files action.

Line 12 defines the target file.

Line 13 calls the “system” body part found in library.cf to set the file”s ownership and permissions.

Lines 14-15 call the “mycopy” body part found in library.cf passing the source file location and the source server. Notice the use of the global variables that were defined in promises.cf.

The file cfbackup.cf file instructs CFEngine to make a failsafe backup of itself. Thus even if CFEngine becomes damaged there is still hope of automatic recovery.

1 bundle agent cfbackup {

2

3 vars:

4

5 "failsafe" string => "/var/cf-failsafe";

6

7 files:

8

9 "${failsafe}/bin/cf-agent"

10 perms => system("0700","root","root"),

11 copy_from => mycopy("${g.workdir}/bin/cf-agent", "localhost");

12

13 "${failsafe}/bin/cf-failsafe.sh"

14 perms => system("0700","root","root"),

15 copy_from => mycopy("${g.workdir}/bin/cf-failsafe.sh", "localhost");

16

17 "${failsafe}/ppkeys"

18 perms => system("0600","root","root"),

19 copy_from => mycopy("${g.workdir}/ppkeys", "localhost"),

20 depth_search => recurse("inf");

21

22 "${failsafe}/inputs/failsafe.cf"

23 perms => system("0600","root","root"),

24 copy_from => mycopy("${g.workdir}/inputs/failsafe.cf", "localhost");

25

26 "${failsafe}/inputs/update.cf"

27 perms => system("0700","root","root"),

28 copy_from => mycopy("${g.workdir}/inputs/update.cf", "localhost");

29

30 }

Line 1 begins a agent bundle called cfbackup.

Lines 3-6 define two variables.

Line 8 begins a files action.

Line 10-29 should look familiar by now. They instruct CFEngine to copy files. There is one noticeable difference. The mycopy call passes the server “localhost&rdqduo and not the central policy server as we”ve seen in the past. The purpose of this is to have the local client backup its own files locally. Thus if the /var/cfengine directory is damaged it will be possible to recover the files from an alternate local location without needing the remote server.

This shell script cf-failsafe.sh is not run by CFEngine but is called by the host, via cron, in the event that cf-agent fails to run.

1 #!/bin/sh

2

3 # This file recovers cf from a very damaged state

4

5

6 mkdir /var/cfengine

7 cp -pr /var/cf-failsafe/* /var/cfengine

8 /var/cfengine/bin/cf-agent && /var/cfengine/bin/cf-agent

9

As you can see this is a simple backup script. Recall that in update.cf we copied selective files from /var/cfengine to /var/cf-failsafe as a backup. This script will be run if cf-agent cannot. In such cases the script will use the contents of the /var/cf-failsafe directory to rebuild /var/cfengine (lines 6-7) and then run the agent twice to finish the repairs (line 8).

Recall that in the cf-execd.cf file we instructed the agent to ensure that cf-execd was running. Then in crontabs-cf we loaded a crontab file. One of the entries in that crontab looks like this.

15 4,16 * * * /var/cfengine/bin/cf-agent|| /var/cf-failsafe/bin/cf-failsafe.sh

At 0415 and 1614 each day cf-agent will be started. If that fails then the failsafe script will be run instead. This is one of the many strategies one can use to ensure that CFEngine will continue to run even the face of difficulty.

Other examples

Now that you’ve seen a basic example, lets look at some further ones to illustrate how CFEngine might be used in production.

Editing files

In this example we’ll edit the NTP time server’s ntp.conf file. We’ll add our own servers to the file allowing for us to define our NTP service across the entire organization. This policy will append three “server” entries to the end of the file “/etc/ntp.conf”.

1 bundle agent ntp {

2

3 vars:

4 "ntp1" string => "tick.example.com";

5 "ntp2" string => "tock.example.com";

6 "ntp3" string => "ding.example.com";

7

8 classes:

9 "ntp_servers" or => { "${ntp1}", "${ntp2}", "${ntp3}" };

10

11 files:

12 !ntp_servers::

13 "/etc/ntp.conf"

14 edit_line =>

15 AppendIfNoLine("server ${ntp1}", "server ${ntp2}", "server ${ntp3}");

16 }

17

18 bundle edit_line AppendIfNoLine(a,b,c){

19 insert_lines:

20 "${a}" location => "append";

21 "${b}" location => "append";

22 "${c}" location => "append";

23 }

24

25 body location append {

26 before_after => "after";

27 }

Line 1 begins an agent bundle called “ntp”.

Lines 3-6 define 3 variables each containing the FQDN of our NTP servers.

Lines 8-9 use our variables to define a class “ntp_servers” and makes our three NTP server members.

Line 11 begins a files action.

Line 12 states that the following actions will be applied to hosts that do not belong to the class “ntp_servers”. Presumably this will match all possible NTP clients.

Line 13 identifies a target file of /etc/ntp.conf.

Lines 14-15 call the “AppendIfNoLine” bundle passing three strings that each contain the word “server”, a space and the name of our three NTP servers.

Line 18 begins an “edit_line” bundle called “AppendIfNoline” The “a,b,c” part defines three local variables that will take the arguments that were passed on lines 14 and 15.

Lines 19-22 denote our strings, a location body part and its name: “append”. This translates roughly to use the defined string at the current location in the file for the “append” body part.

Line 25 define the location body part called “append”.

Line 26 tells CFEngine to insert our string after the current location which in this case is the end of the file.

That did seem quite complicated for a seemingly simple action. It is a lot but keep in mind that CFEngine is capable of far more complex edits. In such cases this modular approach will help greatly.

Disabling files

This example shows how someone might disable an unwanted file. Disabling a file simple involves renaming it and perhaps altering the permissions.

1 bundle agent disableftp {

2 files:

3 "/etc/vsftpd/vsftpd.conf"

4 rename => disable;

5 }

6

7 body rename disable{

8 disable => "true";

9 disable_suffix => ".cfdisabled";

10 disable_mode => "0600";

11 }

Line 1 defines an agent bundle called “disableftp”.

Line 2 begins a files action.

Line 3 identifies our target file, an ftp daemon configuration file.

Line 4 calls a rename body part called “disable”.

Line 7 begins the body part called “disable”.

Line 8 tells CFEngine to disable the defined file. Other actions are possible such as warn.

Line 9 defines the suffix to be added to the renamed file.

Line 10 defines the mode of the renamed file.

Disabling processes

Suppose you want to forbid a process from running on a particular server.

1 processes:

2 secure_hosts::

3 "stunnel" signals => { "term", "kill" };

Line 1 identifies the processes action.

Line 2 identifies that the next action is for members of the “secure_hosts” class.

Line 3 tells the agent to check for a running process that matches the regular expression “stunnel”. If any are found a “term” signal is sent that will hopefully end the unwanted processes. If the “term” signal is unsuccessful then a “kill” signal will be tried instead.